The 21st Century Professor: Sage on the Stage or Guide on the Side?

What makes for better college-level instruction, a face-to-face classroom experience or computer-driven instruction? On the one hand, we all know well the traditional model of classroom learning; it’s been with us since Aristotle lectured in the Lyceum. On the other hand, computer-adaptive instruction is an emerging realm that allows students to set their own pace for learning. Learners adapt the curriculum to meet their needs through personalized and immediate online instruction and feedback. Computer-adaptive learning promises to reach far more students at far less cost than standard, face-to-face classroom instruction. But is something essential lost in the process? The answer has huge implications for the future of higher education.

What makes for better college-level instruction, a face-to-face classroom experience or computer-driven instruction? On the one hand, we all know well the traditional model of classroom learning; it’s been with us since Aristotle lectured in the Lyceum. On the other hand, computer-adaptive instruction is an emerging realm that allows students to set their own pace for learning. Learners adapt the curriculum to meet their needs through personalized and immediate online instruction and feedback. Computer-adaptive learning promises to reach far more students at far less cost than standard, face-to-face classroom instruction. But is something essential lost in the process? The answer has huge implications for the future of higher education.

There’s an expression in my field of school psychology: “In God we trust. All others must have data.” Data-driven research will help address these questions and will drive the future of instruction at the college level. With support from the university and from Doug Gillan, head of our Department of Psychology, I applied for—and received—one of ten grants that the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation made this year to study whether computer-adaptive instruction can work as well or better than standard classroom instruction.

I’ll be working with a graduate student for the next several semesters to test various ways to deliver instruction through an Introduction to Psychology course. And we’re working with two commercial partners: Adapt Courseware is providing us with their computer-adaptive online course and Cengage is providing us textbooks and their online Coursemate. As their contribution to the study, both of these partners are providing their products free of charge.

Students who volunteer to participate will be randomly assigned to either the computer-adaptive version of the course or the more traditional lecture-format classroom version. At the end of our two-year study, we should know how the two groups compare, looking at whether they completed the course, their final grades, and the biggie, how they fare on a common set of final exam questions. We’ll also ask students and faculty how they use their time in each condition, how satisfied they are, and other measures of course activity and outcomes.

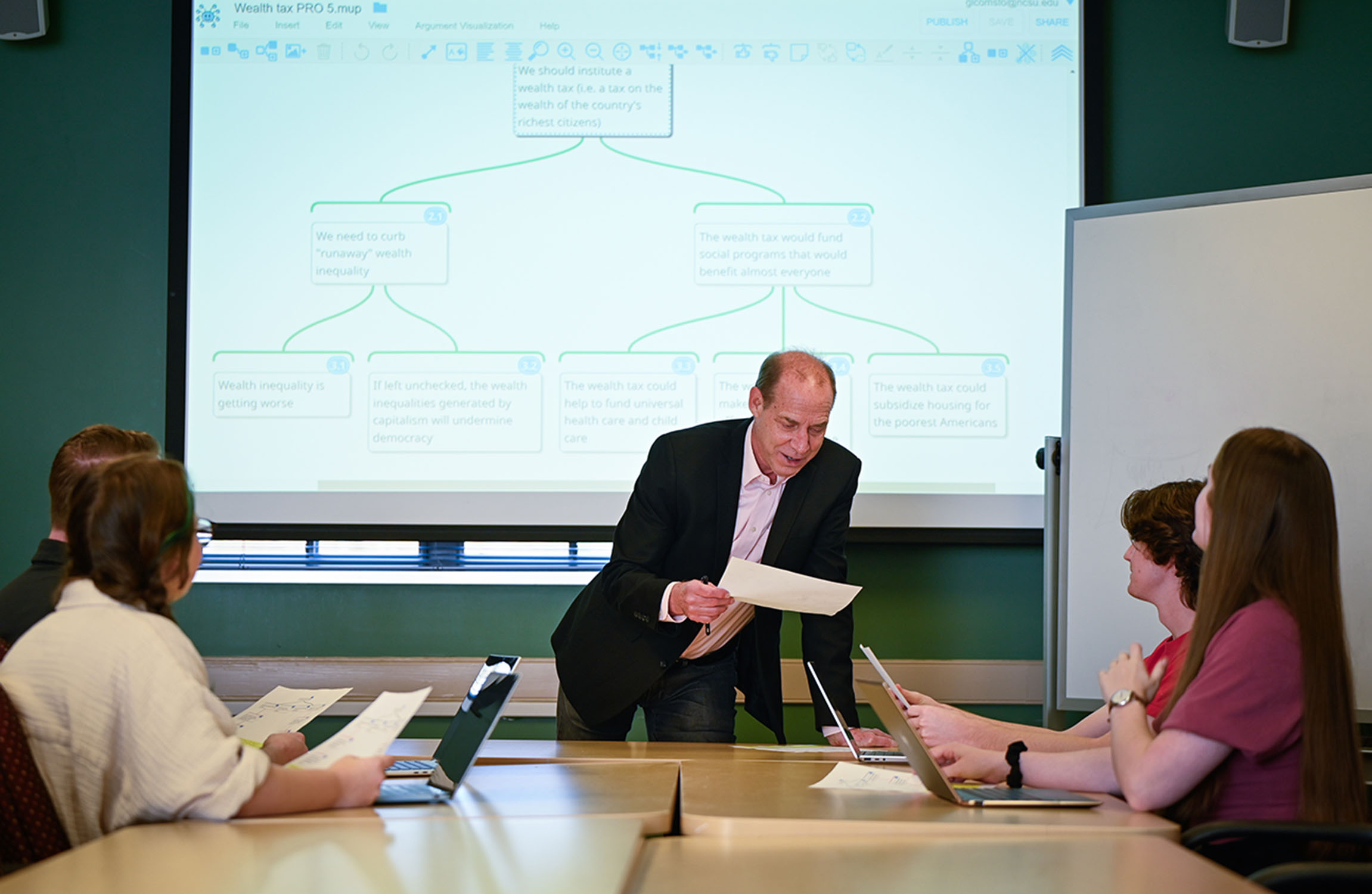

I’m particularly interested in understanding whether computer-adaptive technology will change the role of the instructor from being “the sage on the stage” to “the guide on the side.” That is, is it more productive and beneficial for an instructor to monitor and attend to student learning or to prepare and deliver information?

This study should provide data to answer whether, at least for an introductory psychology course, technology might offer us a better and more cost-effective way to help students learn. That’s of interest to me both as a dean and as a scholar. Inside Higher Education published an essay earlier this year that further outlines issues around adaptive learning.

I’m looking forward to dusting off the research skills that I put on the back burner to deal with budgets, personnel, and programs over the last five years. I also get to lead by example by mentoring a graduate student funded for two years through the grant, which is a welcome resource in these tight budget times.

Even at the outset of the project, I’ve been overwhelmed by the support I’ve received from every single person I’ve asked to help work through technological, logistical, and design challenges. It reminds me how lucky I am to be at NC State—I’ve never enjoyed the level of enthusiasm and willingness to help anywhere else I’ve worked.

This study will help us know whether technology can help us teach—and more importantly, help students learn—at least as well as our traditional methods of instruction. It’s a great example of how the social sciences illuminate the educational value and social impact of technical innovation, and I’m delighted to play a role in this interdisciplinary endeavor.

- Categories: