NC State Lands NEH Grant to Decode Old Texts Using DNA

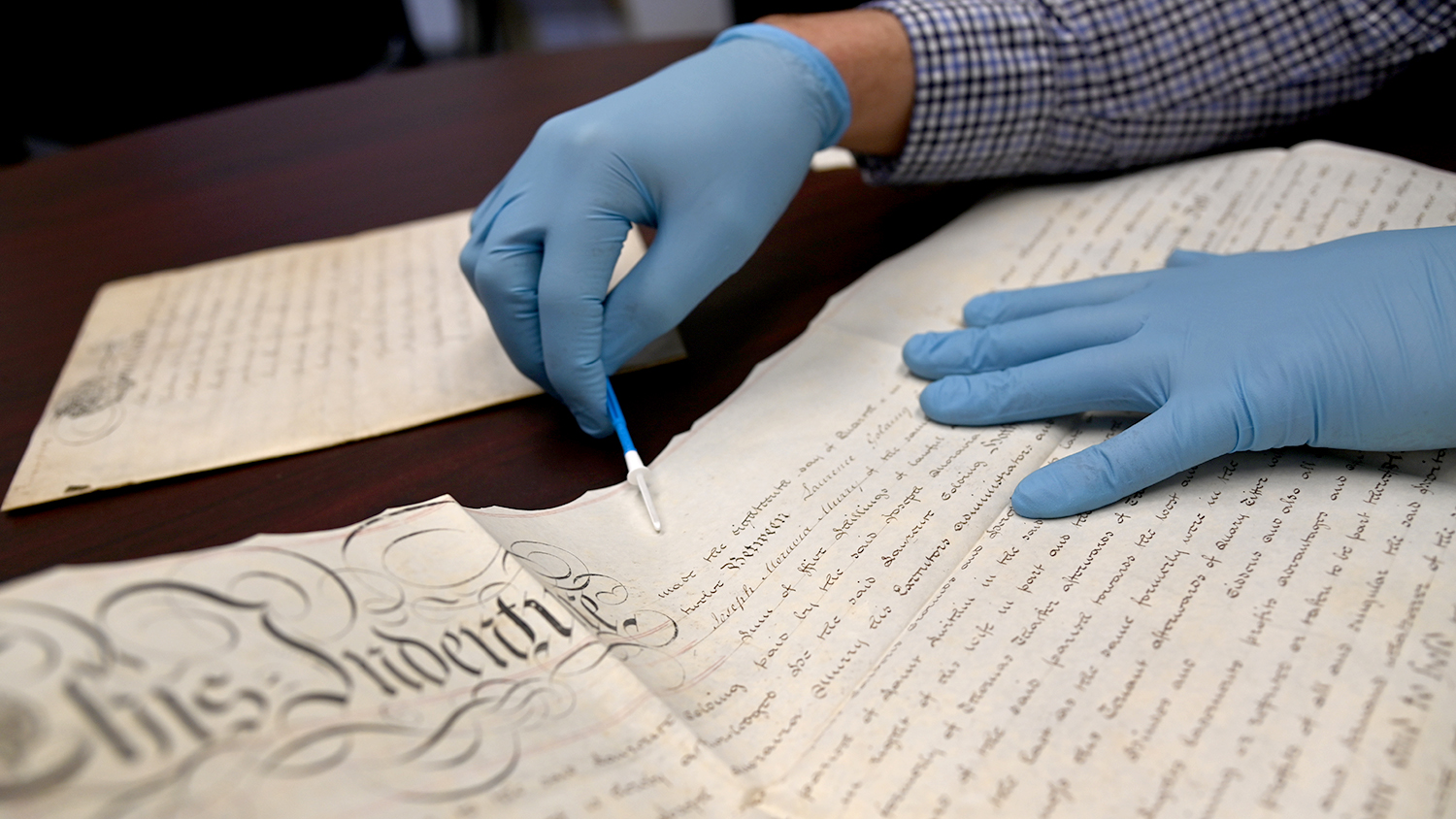

Using a cytology brush to extract samples from a parchment document.

An NC State humanities scholar and university biologists recently received a $250,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to analyze DNA found in parchment manuscripts to uncover new insights into the humanities and encourage partnerships between the humanities and natural sciences.

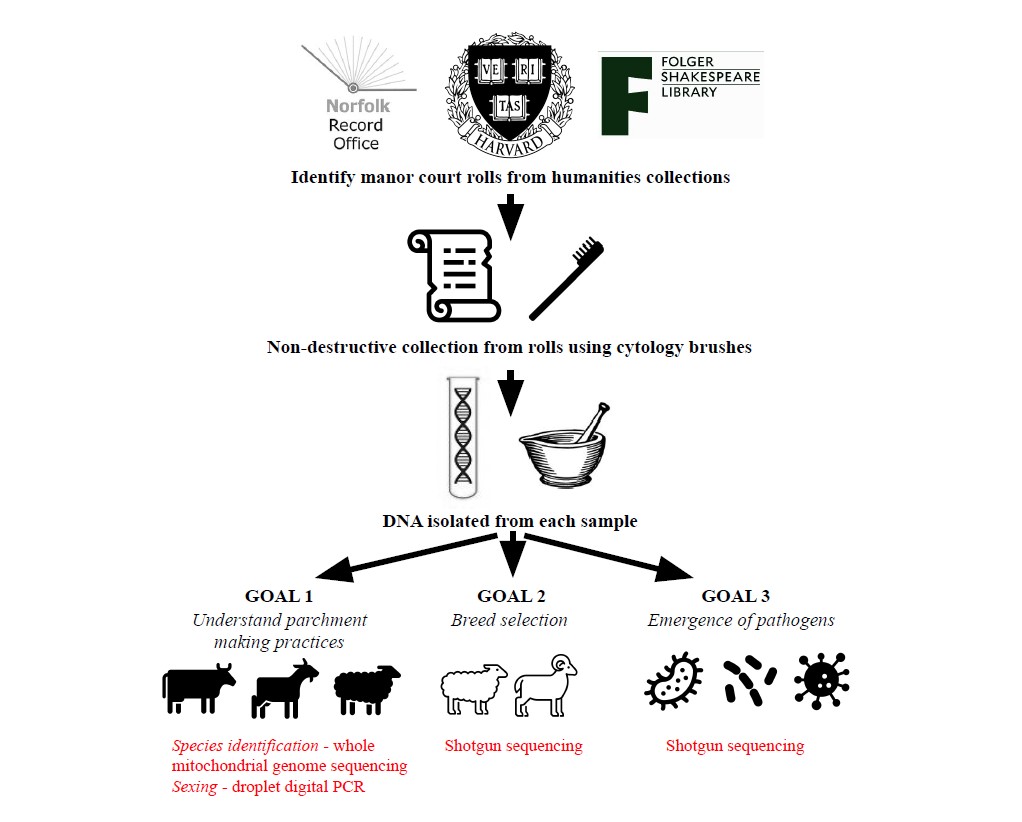

The team, using non-destructive sampling techniques they recently developed for DNA analysis, will pair biological data with textual and historical information found in manor court rolls and probate itineraries from three partner institutions: the Norfolk Record Office, the Harvard University Law Library, and the Folger Shakespeare Library. From the data collected, the researchers say they aim to better understand early modern parchment-making techniques, investigate the history of cattle, goat, and sheep breed selection, and trace the origins of pathogens in early modern England.

“To date, the non-textual data held in these skins remains almost entirely untapped, partly because the documents have always been perceived as repositories of texts rather than biological data, and partly because the tools and techniques to access this information in a non-destructive manner did not exist,” says Tim Stinson, associate professor of English in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences and the project’s director and principal investigator. “Our team aims to change both.”

Joining Stinson on the project team are co-directors and faculty members of the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) Kelly Meiklejohn, associate professor of forensic science; Matthew Breen, professor of genomics and the Oscar J. Fletcher Distinguished Professor of Comparative Oncology Genetics; and Benjamin J. Callahan, associate professor of microbiomes and complex microbial communities.

“The NEH award is truly a remarkable achievement that recognizes the importance of combining the scholarly activities of humanists and scientists.”

“Literary scholars might learn more regarding when and where texts were copied and read,” Stinson says. “Economic historians might learn about parchment as a commodity, as well as the functioning of medieval agrarian society. Environmental historians might gain additional evidence about events such as floods and droughts that we know about from history.”

In terms of veterinary science, Meiklejohn adds: “The potential of genetic studies of parchment to contribute to our knowledge of animal husbandry practices is substantial. This funded study is designed to provide a snapshot of animal populations from a single known locality across several centuries, during which time we know that selective breeding was practiced and being developed, but for which we lack scientific as opposed to textual evidence.”

The current project builds on the team’s earlier work in developing and successfully implementing non-destructive sampling techniques to extract and analyze DNA in parchment manuscripts at Duke University, dating from 700 to 1700 AD. The researchers say the tests were done without damaging the parchment, and permitted the identification of the animal source of the skin.

That earlier work was supported by $25,000 in Research and Innovation Seed Funding (RISF) from the university.

In continuing the research Stinson says it might be possible, for example, to dig deeper to understand the historical emergence of livestock breeds, to find the genetic remains of medieval pathogens, and to discover clues to environmental events such as floods and droughts in the conditions of these skins, and more broadly to understand human-animal relations during the medieval period.

“We are talking about the skins of millions of individual animals, many of them preserved in excellent condition, and from virtually every location in Europe,” he adds. “The amount of knowledge about the past locked away in those skins is simply staggering.”

For this project, the team is using manor court rolls and probate itineraries, focusing on one locality. Manorial rolls, the researchers say, provide highly detailed local accounts of legal, economic, and social history by documenting landholdings, agrarian society, village life, demographic changes, animal husbandry, and the impact of factors such as pandemics, weather conditions, and social upheaval on local rural populations.

Probate itineraries are listings of possessions to document inheritance. Team members will use techniques they perfected in their last study to non-destructively collect biological information from the skins to analyze local herds from one estate over time.

The project is one of 19 Collaborative Research projects, totaling $2.78 million, that the NEH recently funded.

“The NEH award is truly a remarkable achievement that recognizes the importance of combining the scholarly activities of humanists and scientists,” Breen says. “It is one of the most exciting opportunities we have had to place NC State at the forefront of a new field of discovery that has far-reaching implications for our understanding of animal-human interaction over many centuries.”

- Categories: