Digitizing Dickens’s Working Notes

Examining the 19th-century author’s novels through a modern lens.

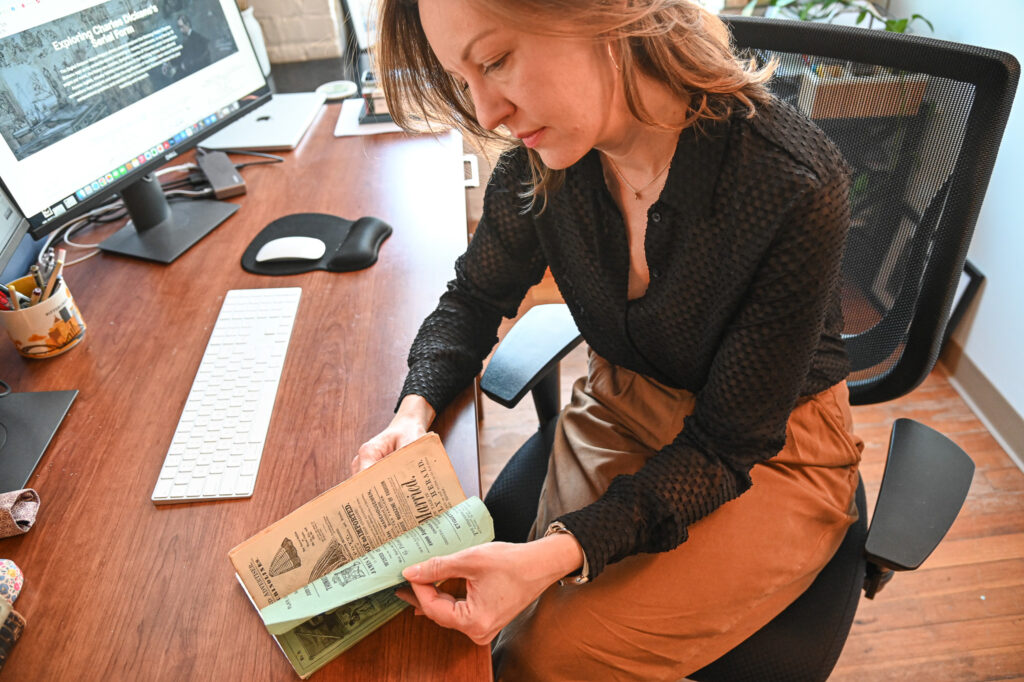

It’s a pioneering initiative: Take the working notes Charles Dickens penned when writing his novels, digitize them, pair them with introductions and editorial comments, and in a first, make them interactive and available online.

In doing so, the Digital Dickens Notes Project (DDNP) offers readers insight into the 19th century author’s creative mind and writing practices and new ways of interpreting texts written in a series. It also provides a fresh perspective on Dickens and makes his novels accessible to a broader audience – from scholars and students to teachers and the general public.

“Rather than reading the notes primarily as planning documents as they have frequently been understood, this project emphasizes their role as dynamic records of the serial process, and creates a way for students and scholars to interact with them,” said Anna Gibson, assistant teaching professor of English at NC State and co-director of the project. “The interpretative annotations explain the significance of each part and help the readers understand the entire novel.”

Joining her as co-director is Adam Grener, senior lecturer in the English Literatures and Creative Communication Programme at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. An inter-university team of researchers, editors and technical consultants also worked on the project, which took eight years to complete. Last year, Gibson and her team posted online the working notes of four of Dickens’s novels and plan to add those of three more.

To understand the value of the project, it’s important to remember that Dickens’s novels were written, published and read in installments. Until the final installment his texts essentially were novels in progress.

With that in mind, the DDNP offers today’s readers a Victorian-era view of what it was like for Dickens to compose his novels over as many as 19 months and in installments, said Gibson.To manage the writing process, he penned notes for each weekly or monthly installment as he wrote it.

The author used the notes to plan future storylines, experiment with character names, establish images and motifs, and track plot developments. He even used them to record personal reminders and to ask himself questions that he would answer at a later time.

“The notes help us understand how each installment functions as a single entity and as part of a whole, offering us insights into how Dickens managed these complex storylines over time,” noted Gibson.

Additionally, when readers click on the interactive online notes they navigate to the specific annotation explaining the meaning behind the note, further enriching their understanding of the novel.

The DDNP also helps illuminate how people in that period read and thought about Dickens’s texts, Gibson said, adding that they also offer a concise way to engage students in a long and complex novel.

”It is easier for students to understand a 900-page novel if you ask them to think about it in parts, which is similar to their watching a TV series,” she added. “Dickens helped make the serial form popular. That’s where we get the modern-day concept of episodes,” she explained.

Like a TV episode, each of Dickens’s installments builds on the previous one and readers anxiously await the new episode to uncover details about the central story.

“One way to help students understand the relevance of Dickens’s novels today is to link his works to TV shows — to this major way students are consuming serial narrative in their own lives,“ Gibson said.

The DDNP also makes the author’s working notes more accessible. Typically, the notes are typed up at the back of the novels, making it difficult for readers to see just how Dickens made use of each page. The size of words and the spacing between them, the choice and number of ink colors, and the use of markings are not easily defined.

”The DDNP both simplifies and enriches the novels for students and scholars.”

Page by page the DDNP, however, offers a tapestry of different color inks, crossed-out words, underlined phrases, check marks and erasures. The only other way to view Dickens’s notes in this manner is in an archival setting, Gibson noted. The author’s working notes are bound with his manuscripts, most of which are held at the Victoria and Albert Museum’s National Art Library in London.

“Our images are not photographs; instead, they provide legible and easy and open access to the transcriptions of Dickens’s notes, facilitating renewed scholarly engagement with these vital records of serial composition,” she explained. ”The DDNP both simplifies and enriches the novels for students and scholars.”

Gibson said she and her team are applying for grants to complete the project, and add new content and technical features. Among them are including images of the manuscript’s pages — and enabling users to toggle between the working notes and those images, and to create their own annotations.

Key takeaways? “I would like to think that a project like the DDNP challenges our assumptions of what scholarship looks like in the humanities and allows for a form of interaction with it that is exciting and accessible,” she said.

- Categories: