We Are the Wolfpack: Meet Akram Khater

After arriving in the United States from Lebanon at the age of 17, Akram Khater set out to pursue a career in electrical engineering. But, like others — particularly those who have experienced the dislocation of migration — his path changed many times.

It is fitting that he now leads the charge to build an archive about Lebanese immigrants. After all, his own journey constantly mediated what it meant to be an immigrant and belong in a strange place he would eventually call home.

Khater grew up in Beirut, in a religiously diverse neighborhood called Hadath that underwent significant changes during the Lebanese Civil War. Violence precipitated his own immigration, but Khater says the catastrophic violence of the war was an episode in his life, not the defining feature of his early childhood.

Yet, as the war escalated, Khater’s family decided to send him outside the country.

Through an organization called Amideast, he applied for scholarships to universities in the United States and won a full ride to Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. His uncle, who worked for an airline, supplied the plane ticket.

“My parents were from a modest income,” Khater says. “My dad took me to the bank, and he drew out all of their savings, which was about $200, to give to me before I left. And that was the last time I ever saw my parents because both of them died about a year after I came to the United States.”

Khater went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from California Polytechnic State University, and master’s and doctoral degrees in history from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the University of California, Berkeley, respectively.

Today, Khater is a University Faculty Scholar and professor of history at NC State. He holds the Khayrallah Chair in Diaspora Studies and serves as director of the Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies, which he helped create.

Read on to learn more of Khater’s remarkable story — and how his life’s work is changing the lives of Lebanese Americans in North Carolina and beyond.

How did you make the leap from studying engineering to history?

I went into engineering not because it was my dream, but because I thought there were only two tracks of life for a young man like myself coming from the Middle East: either you go into medicine or engineering.

So, I pursued it out of financial exigency and not necessarily knowing the other possibilities available to me. As an undergraduate, I completed a minor in women and gender studies. From the first day, I was taken by it because it was about trying to understand the human condition. It was an attempt to think about a more equitable and just world. That’s what we do in the humanities — we constantly rethink and consider what it means to live in a collective justly. The minor in women and gender studies truly laid the foundation for my career. After I started working for Intel, I began taking an evening history course on a lark. And between the two, I felt that the humanities was calling my name.

What brought you to NC State?

After earning my Ph.D., I knew that I wanted to teach, and I had several offers. From the moment I arrived at NC State, I was struck by how amazing the history department is. The collegiality and the brilliance of what would be my future colleagues made an impression on me. I continue to be amazed and delighted by them. There is a culture of support within this department that in itself is profoundly important to me.

How did the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies take shape?

Around the time I became a full professor, I would meet often with a friend, Dr. Moise Khayrallah, who I had known through the Triangle Lebanese-American Center. We would talk about how important it is to share Lebanese history and culture with the community at large. He wanted to provide financial support for these broader ideas, so he asked me to write a proposal. I imagined a way in which we could leverage the strength of the history department to begin to collect oral histories from Lebanese Americans in North Carolina

Dr. Khayrallah generously funded the project, and in its pilot phase, from about 2011 to 2015, we created a documentary and an exhibit at the North Carolina Museum of History that toured across North Carolina. They’re both called “Cedars in the Pines,” a title that reflected the native trees of Lebanon and North Carolina. It was a very successful pilot project. The Lebanese who have been in North Carolina for a while finally saw their story told publicly in a positive way — a significant departure from much of American discourse, particularly post-9/11.

So we embedded the story of Lebanese Americans and, on a larger scale, Arab Americans, into the heart of the story of North Carolina. And for me this is critical because in many ways Arab Americans have been marginalized in the United States. For us to tell this full-bodied story, and to tell it in a place that is about the history of North Carolina, was to place Arab Americans at the heart of American history and narrative. It was a very powerful moment that people really responded to — reaffirming my long held belief as a historian — that there is power in people having access to their own histories.

What happened next?

Because of the success of the pilot project, Moise came to me and said we really need to expand this beyond North Carolina. And of course, I was thrilled. So we proposed an endowed center, one that would guarantee that whatever people entrust us with, we will treat with respect and preserve in perpetuity. Thus, Dean Jeff Braden and Marcy Engler [director of development in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences] were instrumental in negotiating the agreement with Dr. Khayrallah and establishing the center which is named after him.

What does the Khayrallah Center do?

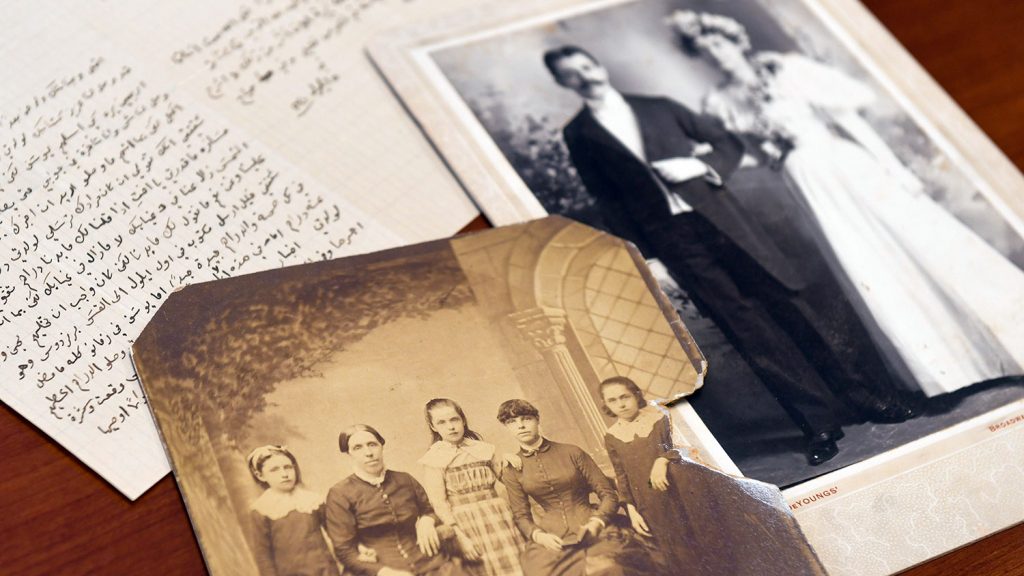

Our mission is to preserve the history of the Lebanese in America and the world, and to share those stories with the general public and scholars. There are multiple layers to our project, but its main foundation is a digital archive that we are building every day. The significance of this cannot be understated. There is nothing benign about collecting archival materials. What some might see as merely family heirlooms or aging documents are, in reality, vital. They are the conduit by which stories get told and which do not. Collecting an archive, both physical and digital, guarantees that certain histories will not be forgotten. And, in history, the process of remembering is always an intentional one.

Together with staff that have been with the project from the start, most notably Marjorie Stevens and Kristen Porter, we have been able to gather a wide range of archival material including newspapers, home movies, photographs, letters, music recordings, objects and oral histories. We collect anything that pertains to the stories and the histories of the people who immigrated from the Middle East and have traveled thousands of miles to make a new life for themselves. We then digitize everything and make it accessible online.

“There is power in people having access to their own histories.”

And we just launched a fully searchable database of Arab American newspapers. This is truly a revolutionary step in the Arabic digital humanities since it will permit for the first time researchers to easily search through hundreds of thousands of Arabic newspapers. At this point our collection spans 17 newspapers, with nearly 300,000 pages. We continue to add to it daily, with a goal to collect over one million pages in the next three years. Imagine what a difference it makes to search for a name and pull up ten different articles, for instance, rather than having to comb through thousands of pages to find one or two of those articles. The ability to search compounds historical research and opens up access in unprecedented ways. And this was only possible because of our ability to work on this project across disciplines, with computer science and statistics professors and graduate students.

Why is this work so important to you?

The fact of the matter is that, for immigrants, belonging in the United States is constantly being questioned. As an Arab immigrant, I have experienced alienation and belonging alternately at different times in my life in this country — sometimes within the same breath. Raising Arab American children in this country was likewise challenging, but I also understand that it afforded them opportunities. In fact, it is the belief in those opportunities and the attendant hopes and dreams cast onto the United States that animate so much of the history of immigration. But, unfortunately, the difficulties and violence that immigrants face when trying to find space to belong are also part of this history. The center’s work strives to engage productively in these conversations while also staking a claim to immigrants’ rights to be in this country and to have their histories told.

How have people responded to the work of the center?

We are unique in that there’s no other center like ours, dedicated to the Lebanese here or anywhere in the world. And we have worked very hard across so many different demographics to make ourselves known. People are hearing about us and coming to us offering, say, letters from their grandmother that have been stored in the attic, because they don’t want those letters to be lost and the stories embedded within them to dissipate.

“We believe that these stories are vital in this world, perhaps now more than ever.“

So, we have developed a level of trust in who we are and that we safeguard the most intimate parts of people’s lives — their memories and stories — with complete respect and professionalism. Moreover, the documentaries, exhibits, scholarship and digital humanities projects that we have produced over the past few years have been viewed and accessed by tens of thousands of people, and the response has been overwhelmingly positive.

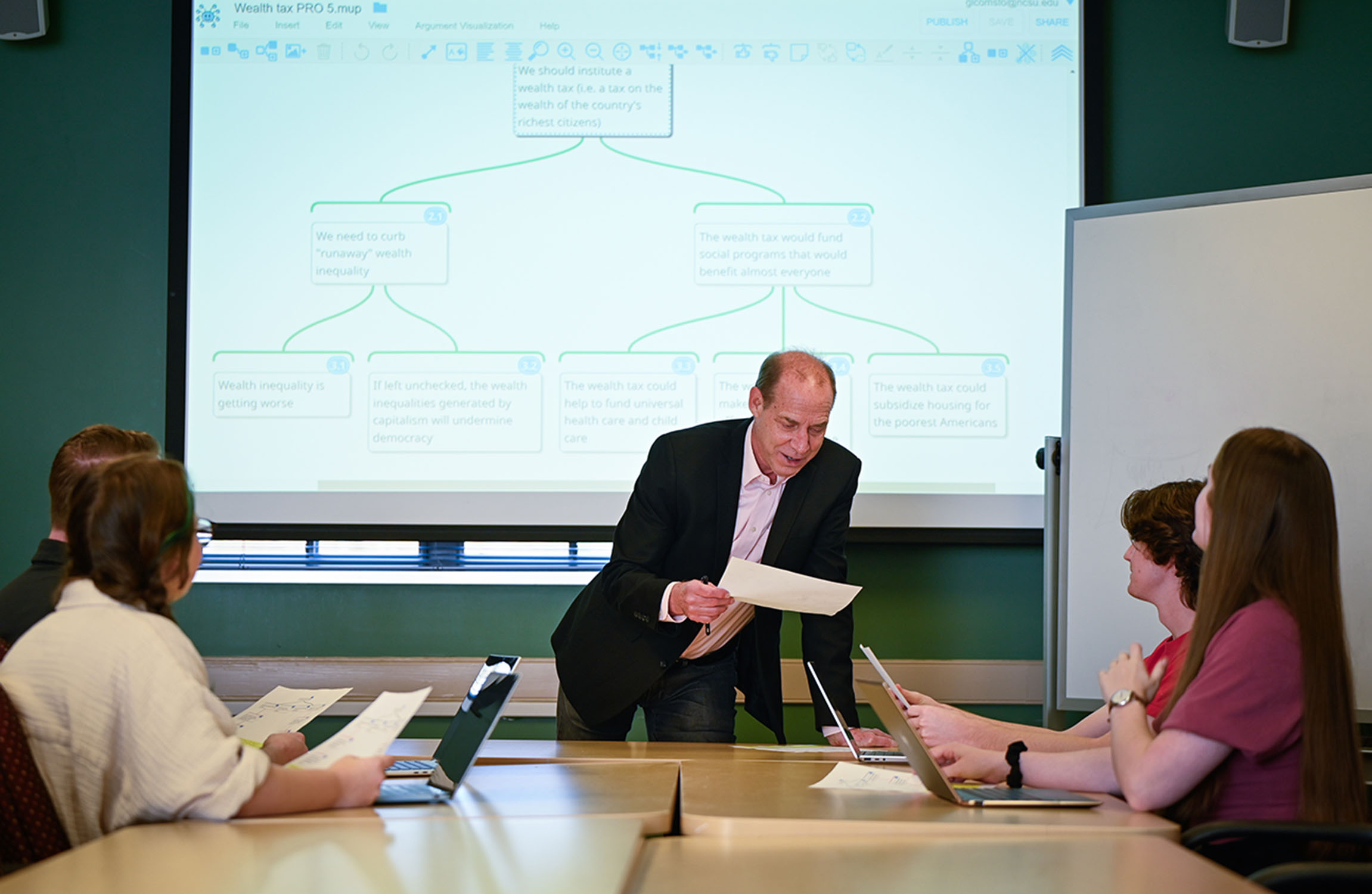

Are you also still teaching while you direct the center’s activities?

Yes, I love teaching. To me, it’s a vocation. I love my students. There are so many things to be depressed about in the world, but at the same time the privilege of being at a university is that you see newer generations of students who are full of promise and dreams, and we’re entrusted with that. To be able to be a small part of their personal and intellectual journey and to help them grow and be good people is an amazing privilege.

How often do you get to go back to Lebanon?

I go once or twice a year because we give the Khayrallah Prize to those whose original artistic work focuses on life in Lebanon or among Lebanese immigrants. We hold the award ceremony in Lebanon, and our hope is that it becomes one of the largest prizes in Lebanon to encourage young artists and writers.

What are your hopes for the future of the center?

I really hope that the center will spur others to action. I hope it will become a model of public history and engagement, and that in doing so it becomes part of a network that encourages people from all over the world to collaborate. We also want to grow the Center, and we will be working over the next 10 years to double the endowment.

We also want the Center to continue to be a great training ground for students. All of our students engage in essential research. Their work and dedication to the center helps to create projects, like the digital exhibit we are currently curating on the history of early Arab American cultural life. The center has become a wonderful humanities lab for a lot of undergraduate and graduate students.

Your enthusiasm is palpable.

I love this work. I can’t hide it. This is my passion because the work we do matters. We believe that these stories are vital in this world, perhaps now more than ever.

This post was originally published in NC State News.

- Categories: